Building Design, December 2009, Review

The fifties were a heady time for America. Abroad, a rising superpower flexing its muscles; at home, a society being transformed through television, air travel, suburbanisation and the birth of what we now call information technology. America was growing in confidence, spurred on by the scientific, technological and commercial optimism of the age.

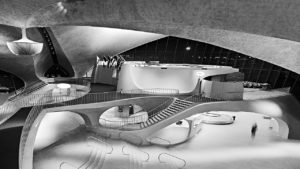

As much as anyone, it was Eero Saarinen who gave physical expression to this new America. His TWA airport terminal in New York symbolised the thrill of commercial air travel. The St Louis Gateway arch, monument to America’s expansionist past, pushed at the limits of engineering. His campuses for corporate America were testament to the country’s financial pre-eminence.

In London and Oslo, Saarinen also had a hand in designing the face of American power in Europe. His US Embassy building in London’s Grosvenor Square attempted to reconcile the country’s competing ambitions to be both dominant world power and good neighbour.

The Saarinen exhibition showing at the Museum of the City of New York offers a fascinating insight into this search for an aesthetic that could, simultaneously, express both egalitarianism and imperialism. A slide-show of early sketch schemes for the embassy’s outer skin include one reminiscent of an opera house, one of an office block, one classical, neo-fascistic, colourful, exuberant. For those who look unkindly on the concrete monolith he eventually designed for one whole side of the neo-Georgian square (controversially listed grade II last month) be reassured — it could have been an awful lot worse.

This show, curated by Donald Albrecht, is the first ever retrospective of Saarinen’s life and work. Made possible by the donation of the Saarinen archive to Yale in 2002, the show has already gone through several iterations. This is its penultimate stop before it finishes in Yale next year.

Represented here is the full range of Saarinen’s work. Although he died suddenly in 1961 aged just 51, not living to see the completion of his best-known buildings — TWA and the St Louis Arch — the sweep of his pen had already been felt across the architectural spectrum.

America’s major corporations were beginning to relocate their headquarters to out-of-town sites. And Saarinen with his building complexes for Bell Laboratories, television company CBS, car manufacturer General Motors and soon-to-be technology company IBM (all companies helping America to claim the 20th century as its own) is credited with inventing the prototype of the landscaped, corporate campus.

It was not just this foray into corporate architecture that formed a stain on Saarinen’s reputation, at least within the architectural world. It was also his chameleon approach to architectural style. With his commercial buildings he formed a close association with his clients (to the point that he referred to them as “co-creators”), causing Reyner Banham to label him the Ad Man and deride him for adopting “a style for the job”. Which wasn’t so far off the truth; Saarinen was one of the first to offer architectural design as brand identity.

Saarinen, along with fellow US architects Philip Johnson and Edward Durrell Stone, was also moving away from the International Style, injecting symbolism, historical reference, questioning the doctrine of form and function and embracing a particularly American appetite for the new.

He was also self-consciously seeking out projects that would place him at the heart of history. His second wife Aline was instrumental here. A journalist on the New York Times, she helped Saarinen achieve his ambition to become not just a creator of culture but a “man of culture”. She introduced him to moneyed families like the Rockefellers and the Havemeyers, the financial titans at JP Morgan, the political leaders and the captains of industry, ultimately helping secure him the prestige projects that made his name.

Today, of course, we know that beneath the veneer of unified progress in fifties America, as expressed in Saarinen’s buildings, irrepressible tensions were building. In contrast to the official portrait America was painting of itself, later a different picture would emerge — of suburban alienation, racial prejudice and cultural hegemony within the country’s dominant institutions. All of which would eventually find release in the social turmoil of the sixties and early seventies. And just as the old certainties fell out of favour, so too did one of the architects most associated with them.

This show, with its rich mix of photographs, drawings, models, and video offers a timely reappraisal. Saarinen was an architect of his age, seeking to break with European tradition and find a new architecture for an emerging power. At times the results were bold, at others simply brash. And just as Saarinen helped define the era, he has also been judged, unfairly, against it. What at the time was seen as stylistic promiscuity, for example, today would be considered diversity, adaptability.

Because of his early death, his buildings offer a snapshot of a particular time. But who knows, had he lived through the following decades he may have responded quite differently to shifting historical circumstances.